Land has always been a highly contested commodity. Indonesia has long faced the serious issue of land grabs, driving indigenous and rural communities into conflict with plantation, forestry and infrastructure developers. Could digitising land records and national geospatial information help resolve overlapping claims to land, and promote agrarian reform in Indonesia?

Land has always been a highly contested commodity. Indonesia has long faced the serious issue of land grabs;farmers’ movements and agrarian reform groups have reported 100 to 200 conflicts per year over land, mostly affecting rural and indigenous communities. The majority of the disputes are within the plantation sector, followed by forestry and infrastructure.

The expansion of plantations, induced mainly by the global demand for palm oil, is the main factor aggravating inequitable access to land in Indonesia. According to data from the Plantation Agency, there are more than 14 million hectares planted in palm oil, comprising more than 50 percent of the country’s arable land.

This is hard to verify, however, since each ministry and provincial government has its own thematic maps identifying land allocated for plantations, forestry, mining, housing, etc. These maps often overlap each other.

Still, a fundamental problem is the structure of land ownership in the country, which cannot be considered equitable or just with a handful of local conglomerates and multinational companies controlling hundreds of thousands of hectares of land. This problem worsened in the midst of the global Covid-19 pandemic, with 241 reported land grabs and evictions in 2020 affecting over 135,000 households; many involved violence.

One map policy

A decade ago, President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono issued a presidential decree to establish a single national map depicting land use. The order, known as the One Map Policy, was made after a heated debate between the Ministry of Forestry and the Ministry of Environment over the definition of forest coverage areas, in the context of a REDD+ project (reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation). The two separate ministries were using different maps at that time.

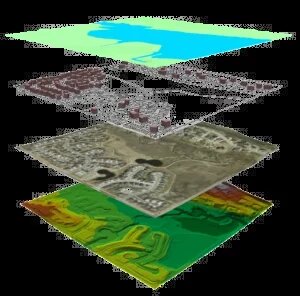

This conflict prompted the government to pursue a comprehensive integrated geographic information system. It was an extensive task to untangle and synchronize dozens of thematic maps across the archipelago, focussing especially on many new permits for plantation, forestry, mining and development projects. The project was not completed during Yudhoyono’s term, and was continued by President Joko Widodo when he was elected in 2014. He entrusted the Ministry of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning (ATR / BPN) to lead the project, using a thematic geospatial reference system to compile, integrate, and synchronise 85 thematic maps from 19 ministries in 34 provinces.

The geospatial reference system, a coordinate-based system used to locate geographical entities, has become a popular tool in the trend to digitise land governance and natural resources. The World Bank has advocated the use of this technology for land governance in many countries in Latin America, for example. In 2018, the World Bank approved a loan of USD 200 million for Indonesia to fund the One Map Policy project, calling it the Program to Accelerate Agrarian Reform. The systematic and complete land registration program was estimated to cost USD 240 million.

Indeed, to solve land conflicts or implement agrarian reform there is a need to tackle overlapping land claims at the government level. Having one national map sounds reasonable for that purpose. Land mapping is necessary and useful when it has genuine participation, where the public can monitor the arrangements of land boundaries and claims. In Indonesia, however, despite its ambitious scope, the process has been largely closed to the public, with datasets mainly provided by government institutions.

In principle, localisation technology and measurement of property limits – the digitalization of land governance – can contribute to the identification of public, vacant, collective/community and private lands. This could help people to reclaim properties that are held illegally. However, land registration in the cadastre without verification by those who live on the land could end up validating historical and ongoing land grabs. The problem appears particularly worrisome since the authorities found that some 40% of the nation’s landmass that has been mapped – over 77 million hectares – constitutes disputed land.

Environmental groups and civil society organisations have also criticised the World Bank loan scheme to fund the One Map Policy project. They argue that the government is following World Bank ideology in considering land as a commodity and fostering land markets. These groups point out that the World Bank has played a significant role in land grabs by financing infrastructure and land-based investment projects and policies for many years, such as the gigantic Kedung Ombo Dam project, and the Wilmar Group’s large-scale oil palm plantation, which received loans from the International Finance Corporation.

Peasants and indigenous communities are left out

Peasant organisations such as Serikat Petani Indonesia (SPI) point out that the One Map Policy and digitalization project has not resolved Indonesia’s main land issues: the extreme concentration of land ownership and the lack of protection of customary rights.

Sarwadi Sukiman, head of the agrarian reform team at SPI, said that the map could not represent reality when peasants and indigenous communities are not involved in its creation. So far, groups like SPI have never been involved in the mapping process.

Instead of supporting agrarian reform, the project thus presented a new challenge to communities and social organisations. As an example, Sarwadi explained how the effort to map territories in Merangin and Muaro Jambi districts in Jambi Province ended up including community-managed areas as part of an industrial tree plantation run by PT Wirakarya Sakti, a subsidiary of Sinarmas Group that controls large-scale tree and oil palm plantations across Indonesia. In Merangin district, 2000 hectares of indigenous territory were claimed as part of the plantation. Local efforts to reclaim this land resulted in only part of the area being returned to the community. The problem, according to Sarwadi, is that the government only acknowledges individual property, and so only land claimed by individuals was given back.

To fairly implement agrarian reform, the One Map Policy project must take into account indigenous territories, which are often ignored by government spatial planning and end up being classified as vacant land, open to exploitation by investors. A civil society network led by the Indonesian Community Mapping Network (JKPP) has undertaken participatory mapping of indigenous territory, and asked the One Map Policy team to acknowledge over 11 million hectares of customary regions, including over 112,000 hectares of land subject to agrarian reform. But to date, customary regions have not been included in the map.

One of the outcomes from the One Map Policy project based on the World Bank document is an electronic land administration system known as e-Land. Through e-Land, the government is expected to issue electronic certificates for plots of land that are already registered as well as for newly registered land. Based on the document, e-Land will provide tenure information not only to the public and government agencies but also to the private sector, including commercial banks, real estate agents, and business developers, especially those involved in precision agriculture applications. The idea is to make investing in land easier, less risky and cheaper, with official land registration and better access to financing.

Both the government and the World Bank insist that the One Map Policy project provides a national information portal as a point of reference for land-use planning by all government institutions and the general public. But in reality, when someone tries to open the portal, it states that anyone other than access holders and mandate holders is prohibited from accessing data and geospatial information through the platform.

According to media reports, the portal is fully accessible only to the president and vice president, the coordinating economic minister, the agrarian and spatial planning minister, the head of the Geospatial Information Agency (BIG) as well as select ministers and representatives of public institutions and local governments. It is impossible for peasant organisations like Sarwadi’s and rural and indigenous communities to access the data.

Conclusion

The quality of information that digital platforms provide is only as good as the data collected. Thus, it is hard to imagine that digital land records such as those generated by the One Map Policy project could resolve perpetual land-grabbing issues or implement agrarian reform. This policy cannot succeed without acknowledging and addressing the problem of the concentration and commercialisation of land, or while restricting public access to relevant information.

The commodification and commercialisation of land, natural resources and the agri-food system are antithetical to genuine agrarian reform, which must acknowledge customary and collective land. Geospatial reference systems do not give instant credence to titles in the public registry offices or legality to land tenure. Beyond individual property rights, customary territory and collective community management need to be acknowledged in the national map. Otherwise, the digitalisation of land use could risk opening the gates to massive land grabs.